Part three of a three part series. You can read part one here and part two here.

It's a hot July evening and we're on the road again. This time we've got two kids in the back seat, bags packed for a week, and passports in the glove box. We're driving to Canada to visit our friends Julie Asselin and Jean-François "JF" Mallette. They're going to let us watch while they dye our yarn.

We head north through the White Mountains. It's a route we've never taken before, and it's beautiful. The sky is a little hazy and when we get a good view we can see layers of mountains fading from green to gray as they get farther away. The day ends with an amazing sunset that seems to last for an hour, the light slowly changing from orange to purple. It fades to black just before we get to the border crossing. Half an hour later we're driving down Julie and JF's street in Coaticook, looking for their house number. From the back seat both kids are proclaiming that they really, really, need to go to the bathroom. Just in time, we see Julie waving from her front porch. We've made it!

Julie Asselin and Jean-François Mallette

Like us, JF and Julie are husband-and-wife business partners in the fiber industry. Unlike us, they are professional yarn makers. They're most known for using hand dyeing to create beautiful and complex colorways. Their designs mix fibers and colors to make yarns that pull you in and reward close inspection. What at first appears to be a solid color reveals itself to be made up of shimmering iridescent layers. Or streaks of pink and green turn out to be made of tiny dots of magenta, purple, orange, yellow, blue, and turquoise. Julie does most of the design, and JF does most of the dyeing. They're both very good at what they do, and we're grateful that they're willing to take time away from their own work to help us out.

Besides being talented, Julie and JF are really fun to be around. They're hospitable, smart, and silly. Their Québécois-French accents are completely charming, and they tolerate our incompetent attempts at French with amusement. In the morning they make us a delicious breakfast of espresso, toast, and home-cured bacon, and then start teaching us about dyeing. Which starts with its own joke:

"So, JF, do you want to tell us about the dyeing process?"

"Well, first you get very sick, then you lie down, close your eyes, and look for a bright light! Haha!"

Colors

After breakfast, we sit down with Julie and look at some color inspiration. We have two colors in mind for our yarn, a gray and a pink, but we need to see some finished yarn before we can make final decisions. We all walk downstairs to their studio to start experimenting with dye.

Choosing dye colors is an art. The color of dyed yarn is a combination of the dye and the natural yarn color, and the ratio of dye to yarn makes a big difference. And in most cases the dye itself is a blend of several dye colors in a different amounts, all of which leads to an infinite number of possible colors.

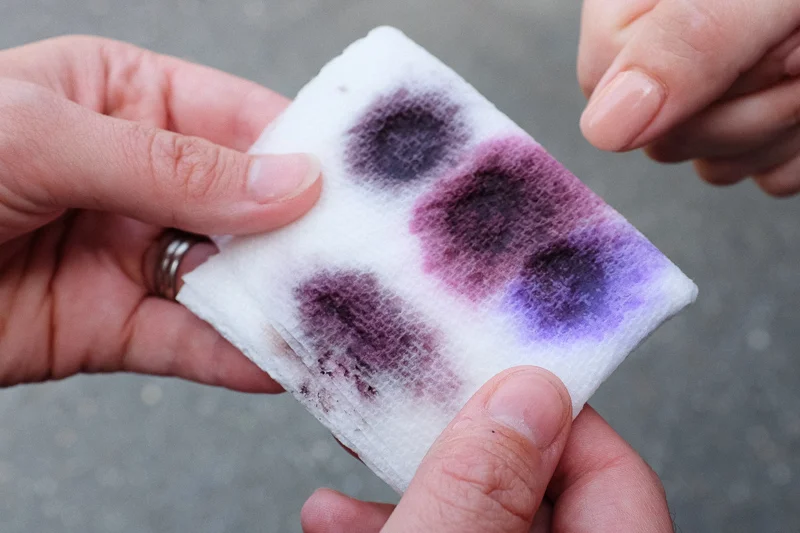

Julie explaining the colors of dye used in our Mussel Gray yarn.

We've decided to work on the gray yarn first. In its natural color, our wool is a buttery yellow, so to neutralize the yellow we'll need some color from the other side of the color wheel: purple. From her library of dye bottles, Julie pulls four colors in varying shades of purple and purply-black. She chooses a different amount of each color and carefully combines them in a measuring cup, checking a scale to make sure she's got the ratio right.

To test the dye mix, Julie combines the dye, water, and citric acid fixer in a glass casserole dish. Then she adds two skeins of our yarn and mixes it up with a gloved hand. She puts a lid on the dish and sticks it in the microwave for eight minutes. Once we're dying for real, our yarn will simmer in a kettle for 45 minutes or more. But for fast prototyping the microwave gives good-enough results.

After coming out of the microwave, the yarn gets rinsed in the sink and then wrung out in a dedicated spin-cycle machine. Then we take the yarn outside to see the results in natural light.

Look at that, it's gray! And an interesting gray at that. We've overshot a bit with the purple, producing a gray yarn with purple undertones, especially in the darker streaks which occur as part of the natural variability of hand-dyed yarn. We love it. We call the color Mussel Gray since it reminds us of a purplish-gray seashell. Our first color is decided! Time to go into production.

Left, undyed natural yarn. Right, our first skeins of Mussel Gray.

"My arm is tired!" Jean-François says, later that afternoon. He's finished dyeing the first few hundred skeins of yarn, and he's washing them in a sink full of cold water before hanging them up to dry. He takes two skeins at a time, dips them in water a couple of times, squeezes out the water by hand, then drop them in the spin-cycle machine. Once the machine is full, the skeins take a spin to remove as much water as possible before he hangs them up to dry. He invites us try doing a few skeins, and it's surprising how heavy these almost weightless loops of yarn become when they're soaked in water. Wool's absorption ability is really amazing.

The following day, Julie and Hannah spend the morning prototyping our pink yarn. Hannah has in mind a specific warm-pink color we've named Rosé, and this time it takes a couple of adjustments to get the the dye mix exactly right. The alternative-pink skeins get set aside for one-off small projects.

Dyeing

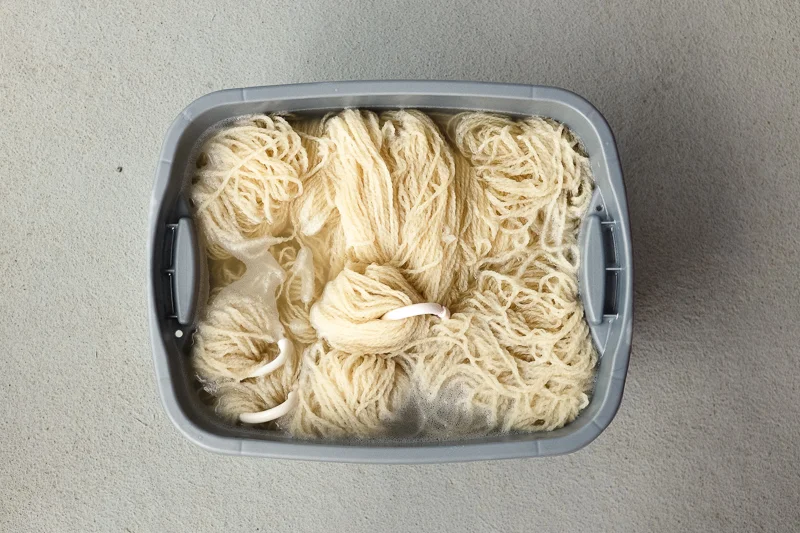

When Julie and JF start dyeing our Rosé yarn, we bring our camera to document the process. It starts with a soak to make sure the yarn is really clean. Any leftover dirt or spinning oil will prevent the yarn from absorbing dye properly.

Washing.

Next, Julie fills a stainless steel pot with water. She measures out the correct amount of our Rosé dye and adds it to the water. Then she sprinkles in some citric acid. Julie says that the dye they're using is specific to protein-based fiber: wool, silk, and other fiber produced by animals. This same dye wouldn't work with plant fibers like cotton. The citric acid fixes it so it will permanently bond with the fiber.

Adding dye.

Next, Julie adds our yarn to the pot, quickly submerging it and stirring it around. Hand-dyeing always results in some variations in color saturation, but there are a number of factors that can be adjusted to make the colors more or less variable. Less water makes for more variation, since dye and yarn are concentrated in a smaller areas and there are more likely to be hot spots. Hotter water also makes for more variation, since the dye sets up faster before it has a chance to fully circulate. In this case, we're aiming for fairly consistent color, so she uses more water, starts it off cool, and keeps the temperature relatively low.

Adding yarn.

Simmering yarn.

The yarn simmers for about 45 minutes. When it's done, the water is clear, since all the the dye has been absorbed by the yarn and been permanently fixed to it. The dyed yarn is squeezed out, spun, and hung up to dry. After it's fully dry, it will get twisted up into a pretty skein and be ready to send off to knitters.

Drained and ready to dry.

Yarn

It's afternoon on our last day with Julie and JF. Our work is done, and we're sitting around sharing a snack and drink before we say goodbye. We talk about Julie's history as a maker and designer, and the difference between a dyer and a yarn maker. At what point can you say you made a yarn, instead of dying somebody else's?

"Nobody is really a yarn maker", says Julie. "Well, unless you're a sheep farmer who also does hand spinning. Most people need to work with somebody else to source the fiber or get the yarn spun. But I think you can say you're a yarn maker if you're involved in every step of the process."

Our conversation expands to the industry in general, and the amount of time and effort it takes to build up a viable business. Julie says the advice she gives people who are just starting out is this: "If you're going to start a business, it really needs to be your own, where you truly believe you're doing something new. It needs to have a purpose."

We reflect on that. Does our yarn have a purpose? Yes, we believe it does. We started this project hoping to learn firsthand about yarn production, and to share what we learned with our customers and readers. In those respects, we'd like to think we've succeeded. We've certainly gained a lot of insight into what goes into yarn making. And if you've been following along, we hope you've found this glimpse of the process as interesting as we have. Thanks very much for taking the time to read this!

And have we lived up to Julie's other standard, and made something new? Well, there are certainly other 100% wool, woolen spun, two ply, worsted weight, hand dyed yarns in existence. But this particular yarn feels like it has its own unique personality. Like the people whose hands have touched it along the way, it's warm, friendly, and hard working. It's beautiful, but it's not fussy. It didn't come from the fanciest of sheep, it wasn't spun on the most modern of equipment, and it wasn't dyed using the most efficient or precise process. But we wouldn't have had it any other away.

Hold a skein under your nose and inhale, and it's all there. The sheep at Noon Family Sheep Farm. The vegetable-based organic spinning oil that kept the wool moving through the machines at Green Mountain Spinnery. The colorful dyes in Julie and JF's studio. We take a sniff and can't help but smile as it all comes back to mind. We hope that smell puts smiles on the faces of knitters, too, as they imagine where their skein of yarn has been, and then start knitting their own chapter into its colorful history.

Our finished yarn. Left, Rosé. Right, Mussel Gray.